In which context are you working as an art educator?

Clare Butcher: I’m working as an education coordinator for documenta 14 in Kassel and just finished a job teaching Masters Education in Art students in Rotterdam about Reading, Writing and Research Methods.

With whom do you cooperate?

CB: I’m working with a great and diverse team of educators here in Kassel, but also in Athens right now.

What is your understanding of art education?

CB: This is a complex question to answer as concisely as I wish I could. A colleague once shared a riddle with me:

STAND

I DON’T

Stand, I don’t…Or rather I don’t under stand. I don’t understand.(1) These words are so profoundly effective in terms of learning moments. To announce this is the beginning of a self-educational process: one that starts with honesty and hopefully goes somewhere we couldn’t imagine. I’m not someone who insists on the resolving of that non-understanding into a fully understood standing position. But rather, the capacity to remain curious, to remain humble, to not understand in front of the other…be that an artwork, a stranger, a crazy idea. As someone interested in educating myself and learning with others, I have to admit my own lack of knowledge on an almost daily basis. Could this be called a methodology? I’m not sure, but I’ll continue to practice this.

What is the relationship (for you) between education and art?

CB: In relation perhaps to my last response, often the great capacity of many artists and artistic projects/processes is their tendency to throw easy comprehension to the wind. The time and vulnerability required to produce a work of art or an exhibition for that matter, or a publication…let’s say, the life’s project (see Boris Groys’s great essay on ‘The Loneliness of the Project’!), almost requires that we – as on-lookers, on-thinkers, cohabitants of the space of that project – make more time and make ourselves more vulnerable to the empathy, the complexity, the journey, the work, that makes art possible. This process can indeed be brought about in other fields…and fortunately art’s unwieldy borders tend to cross over to so many of those!

Why mediate (contemporary) art? / Why educate people about (contemporary) art?

CB: There’s a tricky assumption that is surprisingly persistent about the relationship between art, education and betterment or upliftment. Maybe it’s the use of words like impact, inspiration, enlightenment, empowerment, which often accompany so-called “creative endeavors.” I recently shared a number of artistic interventions into the urban mélange of downtown Johannesburg with some Geographic Science undergraduates at Wits University. In the discussion that proceeded, I was asked “Is that it, or did the projects actually change something?” Of these ephemeral and often playful actions, I couldn’t really say that they had changed anything other than perspective – of the artists themselves, those involved in the action, and perhaps those watching (and us, looking at the documentation). And perspective – something most people might learn on the first day of art class, with a pencil in hand when asked to draw what they see – is no small thing. It’s about how we see the world. To engage with the construction of that perspective is indeed a critical task and the reason that I recommend everyone goes to art school: get some perspective(s).

In what kind of relationship do you see the practice of curating and educating?

CB: #educationalturn. This is a bit of a bugbear of mine as I was trained as an art historian and curator, but have in recent years, ceased to introduce myself as such. While both curating and educating share a common interest in collecting, arranging and sense-making, I think the intention behind the practices can be quite different in terms of the questions they are led by. While often there is not a distinction between curators of exhibitions and of education or public programs in museums, the prompts of “for whom?”, “so what?” and “how come?” which open up collections for extended conversations are not always the remit of a curatorial team. So far, the many manifestations of the “educational turn” in exhibitions which I have encountered have assumed a much more stylistic approach to the work of education (usually involving reading rooms made of raw wood, chalkboards, key theory books, etc.) rather than the active (and sometimes invisible) work of developing an inclusive pedagogical program. Of course, we could go back to the root of “curate” (to care for, to cure), but that care sometimes needs a few critical appendages to become part of a more public curriculum.

Where do we find the (institutional) spaces, in which we can have a discussion about our experiences of art?

CB: I have been convinced for a long time that kitchens make the best spaces for discussion, about art and the many tangents relating to it. There’s a great history of eating and talking about ideas and abstract things from the Greek symposiums to the present. In Spanish there’s even a specific term for the kind of rich conversations that happen over dinner tables – “sobremesa.” As opposed to the often quite stale conditions of a lecture theatre or seminar room, kitchens (which I’m using quite broadly now to mean intimate, productive, potentially messy spaces, in or outside) allow for other sorts of factors to enter the frame, such as hunger, togetherness, smell, touch, taste, and marinating over time – all ingredients of living with and around art.

To what extent can art education and art mediation open up a new sphere of action?

CB: I used to have ambitions of being a theatre maker and though he’s too often quoted, the thoughts of playwright and director, Berthold Brecht, are useful for me in relation to this question of action. In the “Messingkauf Dialogues,” where Brecht basically has a long conversation with versions of himself, he wrote about the potential of a representational scenario to instigate a process of self-recognition and with that, the possible shifting of habitual behavior (on an individual level). In connection to what I mentioned earlier about the impact a shift of perspective can have, the possibility to reprogram our habits in the world is not one that comes along often, but usually happens when there’s a moment of rupture, interruption, making the familiar strange or displacement – quite violent in nature actually. All of which are necessary to jar us out of our comfortable routines, make us consider, for a moment, the contingency of things, but also the long lines which might connect them. Art and, I think specifically, art education (I’m using education here and not mediation), can create such conditions in the flow of everyday, allowing us to imagine what could be…not only individually as in the Brechtian example, but together. I like the words “contingency” and “coincidence.” After reading the terms through the eyes of writer Lewis Hyde, I came to see their connection more and more. In his text Trickster Makes This World Hyde talks about con-tangere (‘two things touching’) and co-incidere (‘two things “falling together”’), which speaks to me of unlikely bodies (people, events, ideas) falling together, or just touching, in a way that might change the course of events in a manner less lonely than Brecht’s ‘A effect.’

When do you think art education is successful? When do you think art education is complicated?

CB: I’m struggling to relate these questions. The second suggests the answer to the first. It’s difficult to measure the success of art educational processes, because art education is complicated. And by complicated I don’t mean confused, or vague, or the all-encompassing “complex.” Rather, that it is implicated within a whole, together with other processes and conditions, which make assessments often superficial and final “outcomes” hard to see. I know it’s useful to measure things, to be able to compare programs and work…but I am of the opinion that the criteria is the issue here. Shall we make a new protocol? A new word that isn’t “success”? Or can we set the general bar at: if no one is harmed or does harm in the process – it went well?

Is there a specific method or strategy you currently work with?

CB: I mentioned kitchens and eating together before. Other methods I’m exploring right now involve more of the body within thinking processes – I’m inspired by Simone Forti’s “Logomotion”, which combines speaking, research and movement. I’m not a trained dancer, but fortunately my students have been equally imperfectly enthusiastic. Also, I’m investigating a few teacher-couples in art and architecture history, who, most often, would only be given one professorial seat or would not both be credited for the work emerging from those professorships. I guess there’s something of the domestic, the retroactive and feminist that runs throughout these interests.

What are you currently working on?

CB: documenta 14 keeps my hands and head full!

Which books and projects are important for your work and why?

CB: I’m enjoying the great research done on the “really useful knowledge” project from the Reina Sofia in Madrid last year. Also the ongoing project of reevaluating the university as an accessible educational structure in so many South African cities and towns (#feesmustfall, #luister), and of course, the many other critical practices I am encountering as we research various educational models for documenta 14.

Which questions would you like to ask an art educator?

CB: I would like to ask what they think a curriculum is/could be.

How do you imagine the future of art education?

CB: Bright.

Clare Butcher is an art educator from Zimbabwe, who cooks as part of her practice. She is currently coordinator for education with documenta 14, before which she taught at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, the Piet Zwart Institute’s Masters of Education in Art, and the University of Cape Town amongst other learning institutions. Her own education includes an MFA from the School of Missing Studies in 2015, a Masters in Curating the Archive from the University of Cape Town in 2012, and participation in the de Appel Curatorial Programme in 2008/09. She was a guest curator with the Van Abbemuseum, where she also served as co-curator of the “Autonomy Project” (2010–12). Other collaborative and individual endeavors include Men Are Easier to Manage Than Rivers (2015); Historical Materialisms (2014–); Every Great Undertaking Has Its Ups And Downs (2014); Scenographies (2013); The Principles of Packing… on two travelling exhibitions (2012); and If A Tree… on the Second Johannesburg Biennale (2012).

Footnote 1: From “Stand, I Don’t: An Interview with Charles Esche,” in Curating and the Educational Turn, eds. Paul O’Neill and Mick Wilson. Open Editions, 2010.

Published: September 21st 2016.

Interview: Cynthia Krell, Gila Kolb

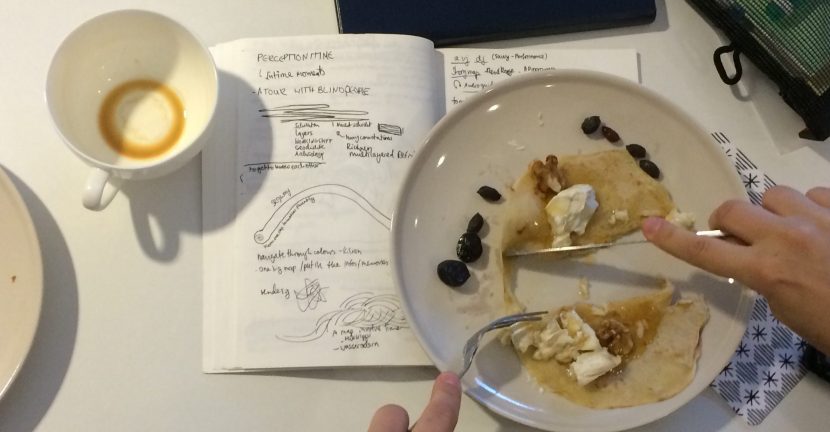

Image: Pancake topographies, mapping the city with students in Kassel, April 2016 by Clare Butcher.