In which context are you working as an art educator?

Luis Camnitzer: I’m an artist, and, one way or another, everything I do is art. That means that I hold art as a reference for rigor: how interesting a problem may be in terms of expanding knowledge, how well a solution fits it, how well the solution is packaged for communication, and how generative it is once communicated. With this as a platform, the educational part becomes crucial and indistinguishable from art. The separation between art and education becomes meaningless. In my older age it seems more efficient to spend time and energy on discussions about education than making little things to be displayed on a wall. Therefore writing and lecturing has taken over the making of things.

Who are you working with?

LC: Some years ago I was the pedagogical advisor for the Cisneros Foundation with their program “Piensa en arte-Think Art.” I worked with María del Carmen González and Sofía Quirós, who were in charge of the educational part of the collection. When the Foundation decided not to pursue education anymore we became independent and, though given the rights to the “Piensa en arte-Think Art” title, we changed the name of the team to “Art as Education-Arte como Educación.” We did the Teacher’s Manual for the Guggenheim Museum’s exhibition “Under the Same Sun,” the manual and pedagogical display for Casa Daros’ Cuban Art exhibition in Rio de Janeiro, and the new pedagogical display for the Museo de Numismática in Costa Rica. Besides that, I write and lecture about art as meta-discipline and other topics.

How would you describe your understanding of art education?

LC: Traditionally, the concept of art education is focused on appreciation and making. I believe it should be about cognition (in its broadest sense). I believe in something that for several years I have called “art thinking.” This is unrelated to the competition of artists in the market or to the development of sophistication in the consumer base of museums and galleries. Instead it is a way of confronting knowledge with unbound and limitless imagination, to question systems of order, to look for alternative systems and unlikely connections, and to only then start negotiating feasibility in real and functional everyday life. Within this frame of a general curricular construction, art as a fragmentary production discipline presents us with interesting or uninteresting solutions that may or may not help us deal with reality and with the order/disorder of the Universe.

How would you describe the relation between education and art?

LC: Personally and given the above, I don’t see any difference and I wish that artists would consider themselves also as educators, and educators also as artists. Otherwise artists are reduced to working on self-therapy, and educators continue working as trainers and transmitters of information.

Why mediate (contemporary) art?

LC: First we have to be aware that all art was contemporary when it was made, and that when going back in time we lose that contemporariness. We therefore are left with semi-inscrutable palimpsests with which we construct the history of art. By addressing contemporary art we have contemporariness at hand and can not only identify that what we don’t understand, but also the reasons for not understanding. This availability allows us to pursue the research in a way that is not limited to the objects we are presented with, but to all conditions and interests that generated them, and to understand the distribution of power and the interests they are serving. Sifting through that salad of conditions we may extract tools that help us in expanding our own knowledge, but also in perceiving how the society we are living in is constructed. When we deal with non-contemporary art, we project the present onto the past. If we studied the history of art from the present backwards, instead of how it’s taught, we would be made conscious of that projection and understand what we see from a contemporary point of view instead of living the fiction that we actually understand what was done in the past. We are always making the mistake of stressing “art” over “contemporariness” and thus distorting our perspective.

Please describe the relation between working as a curator and working as an art educator from your point of view.

LC: Again, I don’t see a neat separation between both. Unless the curator limits the work to art handling (just hanging the work in a pleasant way) or to the promotion of the personal ego (establishment as a diva), the activity is to help artists communicate with the public. It is an educational task accomplished by a good use of taxonomies and by having works and spaces act as resonance boxes, all of which actually make that the act of mediation becomes as invisible as possible.

How important is art education and mediation for a museum / an institution?

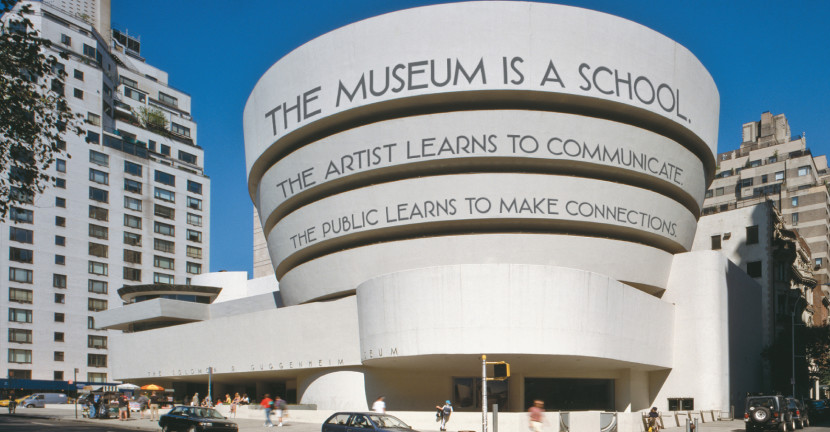

LC: Today few museums would still define themselves as “show-off” institutions (even if most [of them] may be) and rather want themselves to be known as “show” institutions. The purpose of showing then becomes an educational task. This is partly acknowledged and they pride themselves of having an educational program. However, the way it’s done is very hypocritical. Educational programs are segregated from the curatorial activities and used as public relations offices. Focus is on expanding the consumer base as shown by circulation numbers easy to use for funding, rather than trying to have transformative effects that cannot be quantified. Working as a pedagogical curator for a museum I once proposed a project for the pedagogical presentation of an exhibition. This prompted the director (with applause of the curator) to say: “This is a museum, not a school.” My reaction (besides resigning) was to come up with the statement: “The Museum is a School; the artists learns to communicate; the public learns to make connections.” Using Photoshop I superimposed it on the façade of the museum and sent the picture to him as revenge. I then realized that there was more to it, and now I’m trying to get the text on the façade of as many museums I can, and presented as official museum statements.

Which institutions provide the opportunity to discuss our personal experiences with art?

LC: I think that it happens mostly in classrooms in universities. The problem is that wherever it happens, it’s expected that one talk about personal anecdotes towards the construction of an autobiography, rather than confronting real issues of general interest and consequence.

To what extent does teaching/mediating art provide the opportunity to concrete actions for the audience?

LC: It depends how it’s done. The main aim should be to equip the public so that people become able to question and demystify, to explore the borderlines of their own knowledge and see how those borderlines may be moved outward. That is where “art thinking” is more important than “art making.”

In your personal opinion, what are the criteria for successfully mediating art? In your point of view, what is especially difficult about it?

LC: Mediating art, the same as making art and presenting it, has to be done with the awareness that there are infinite publics, not just one, and that communication has to be fine tuned for the public one is addressing. True success is probably impossible to ascertain, measure would be by checking transformation, something that the individual wouldn’t necessarily be aware of, or by the length of collective chain reactions. We are really talking about cultural effect and not about fickle personal answers.

Have you developed a special method or innovative strategy you’re working with?

LC: When dealing with finished art works I try to not start working with the piece, or to look “through” the piece, but to go around it and see what the conditions are that made the existence of the work inevitable and indispensable. The public is then confronted with a problem to be solved. They should try to solve it anyway they want (art or non-art, the word “art” does not appear yet). With that, the public is embarked in the same process the artist was from the very beginning, and that makes them colleagues rather than consumers. To this effect I present a problem that might have originated the work, then open exercises that are related to the problem, but that don’t require art to be worked on, and only after that is done, I show the work of art that initiated the process. At that point the public may decide that whatever they did is better or more accurate, or may be impressed by what the artist did, or by the fact that art was a medium to do it. In either case, there is horizontal dialogue established with artist, rather than a vertical passive acceptance of a ready made object.

What are you working on at the moment?

LC: I’m working on a book tentatively called “Art Thinking” together with my son Gabo Camnitzer (he teaches at The Valand School of Fine Arts, University of Gothenburg). I’m giving lectures and critiques, and also preparing a retrospective exhibition of my work for the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, in 2018.

Luis Camnitzer is a Uruguayan artist born in Germany, 1937. He immigrated to Uruguay when one year old and lives in U.S.A. since 1964. He is a Professor Emeritus of Art, State University of New York, College at Old Westbury. He graduated in sculpture from the Escuela de Bellas Artes, Universidad de la República, Uruguay, and studied architecture at the same university. He received a Guggenheim fellowship for printmaking in 1961 and for visual arts in 1982. In 1965 he was declared Honorary Member of the Academy in Florence. In 1998 he received the “Latin American Art Critic of the Year” award from the Argentine Association of Art Critics and in 2002, the Konex Mercosur Award in the visual arts for Uruguay and in 2011 the Frank Jewitt Mather Award of the College Art Association and the Printer Emeritus Award of the SGCI. In 2010 and 2014 he received the National Literature Award for Art Essays in Uruguay. In 2012 was awarded the Skowhegan Medal and the USA Ford Fellow award. He represented Uruguay in the Venice Biennial 1988 and participated in the Liverpool Biennial in 1999 and in 2003, in the Whitney Biennial of 2000 and Documenta 11 in 2003. He was the Pedagogical Curator of the 6th Bienal de Mercosur in 2007. His work is in the collections of over forty museums, among them Museum of Modern Art, New York; Metropolitan Museum, New York; Whitney Museum, New York; Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas; Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, Sao Paulo; Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires and the Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo de Costa Rica. He is the author of: New Art of Cuba, University of Texas Press, 1994/2004; Arte y Enseñanza: La ética del poder, Casa de América, Madrid, 2000, Didactics of Liberation: Conceptualist Art in Latin America, University of Texas Press, 2007, and On Art, Artists, Latin America and Other Utopias, University of Texas Press, 2010.

Image: “The Museum is a School; the artists learns to communicate; the public learns to make connections.”, 2011. © by Luis Camnitzer.

Published February 15th 2016

Interview: Gila Kolb, 2017